Actually, I think Art lies in both directions – the broad strokes, big picture but on the other hand the minute examination of the apparently mundane. Seeing the whole world in a grain of sand, that kind of thing.

–Peter Hammill, English Musician

There are smaller stories everywhere and a world waiting to be discovered beyond the big picture. I know. I find them every day. One thing I have learned and know about myself is that I am far better at finding and seeing the smaller stories than I am at seeing the big picture. I’m detail oriented (not perfect). I pay attention to and notice the little things, sometimes to my detriment. I love words and writing but lean more toward the poetry and short stories. The idea of writing a novel is daunting, though someday I may. I also love capturing my world in photographs, ones that reflect inward motion more often than wide expanse. Even in the beginning of my photographic journey, I was drawn to the details, the overlooked, often unnoticed parts of a scene, place or subject.

My landscapes are more often intimate than grand. In fact, in my early days of photography, the grand landscapes were often “too much” for me to handle with the camera for a variety of reasons. I could see them, even feel them, but the awe and wonder that the grands evoked were elusive in my images. I didn’t know how to “manage” the visual and emotional overload – technically or creatively. I am better at it now, but realize and embrace the reality that I find my best images in the smaller stories. Those are typically the ones that resonate and capture what I see and feel. That doesn’t mean that they’re all in the macro world (which is my Calgon), but simply beyond and within the big picture.

WHAT DOES THE SMALLER STORY LOOK LIKE?

It depends, in part, on the bigger picture or place. It’s incredibly relative. If we’re talking about a field of wildflowers, the smaller story is found in the singles and the small bouquets. It is found in the butterfly feeding on nectar, the caterpillar eating leaves, the birds perching and flying among the sunflowers. It is found in the petals and leaves and ladybugs. If we’re talking about the rural landscapes (common scenes where I live), then it is made up of different elements. It is found in the barns, fences, tractors, farm implements and parts and pieces of all of these. It is found in the fields filled with crops of the region and the season. It is found in the farm animals – cows, horses, goats, chickens – and all that comes with them. Think of the feeding stations, the metal buckets, wooden crates. The smaller story is even found in the farmer and farmhands working the land.

You can find the smaller story, even if you’re most comfortable with the grander landscapes. You just might have to work a little harder if doing so doesn’t come naturally to you. For me, breaking down those scenes is easy. And, the beauty of this approach is that I’m not locked into a timetable of the “best light, best time” scenario. It’s the same for you. All day long, every day, there is something to see and discover and capture. Yes, “great” light is magical, but it isn’t on a menu for us to order up whenever we want it. We need to be able to capture images that speak to us and be in the moment no matter what light we’re given.

Look for the good stuff. Use the tools we have to add, hold back or change the impact of the given light. Some words of encouragement that follow, and a few practical tips for finding the smaller stories, may help you come away from almost any shooting experience with images that you really like, that surprise you (given what you may have had to work with), and a greater appreciation for the “smalls.” You can do this, and you can learn to do it well.

WHERE AND HOW DO YOU BEGIN?

So, what’s your first step if you’re more of that “big picture” kind of person? Bear with me here, and embrace the challenge. Whether you’ve been a photographer for a long time or you’re just trying to figure things out or you’re somewhere in the middle, the following “mindful moments” exercise gives some guidance. And, when you do the exercise, let me know how it works out for you. Keep in mind, part of this challenge includes your looking at “sucky light” as an opportunity and not an excuse to stay in bed, stay home or turn around and go home.

Start Here:

Pick a day and time to go out in the field to photograph. Commit to the date regardless of the conditions. If it’s a “blah” day at a location you frequent more for the grander landscapes, the scenes that ache for the right light, dramatic clouds and such, GO ANYWAY. Accept that the light and weather is not “perfect” for the images you commonly strive to make and enjoy the most. Again, go anyway, but shift your focus and get a grip on your attitude. Be open to seeing differently.

When you get to “the place,” find a spot. Then, simply sit down and get comfortable or stand there, if you choose. Leave your camera alone. You can keep it with you, but resist the urge to turn it on, attach it to your tripod or even give a quick peek through the viewfinder. Take in the views all around you, starting with that big picture you like so much.

Now, move from the bigger scene – the grand – into noticing the smaller pictures. Direct your attention from the forest to collections of trees to single trees and then to the branches and limbs and down even further into the leaves. Notice the colors, patterns, textures, relationships between the elements. These are the same things you would also include in your grander landscape images. Push yourself to notice more and stay with it. Now, do the same with the ground surrounding you, whether filled with boulders or grasses or flowers or agricultural crops. What are you sitting on and among? Focus on each space, one at a time, and continue the process of breaking things down into smaller and smaller scenes and stories.

Pay attention to what you see and feel (physically, mentally and emotionally). Raise the level of your awareness. Close your eyes if you need to. In fact, go ahead and close them, removing all distractions. Take it all in. Be there for the sounds and sensations. Is there a breeze where you are sitting, or is it fixed with stillness. Is the temperature warm, hot, cool or cold? Can you feel the sun on your face? Can you smell the pine trees or honeysuckle, the grasses or even the dirt? What do you hear? Are there birds chirping, water running, rain falling or leaves rustling? What about traffic or other noises. Do you hear the sounds of an airplane, tractors, metal banging loosely on an old building? Does any of what you sense bring back memories? How might that change how you interpret the scene?

And when you’ve done all these things, open your eyes. Don’t press the shutter a single time until you’ve had the chance to absorb all you’ve seen and sensed. Give yourself the opportunity to stay in the moment and be present. When It feels right, start shooting. Shoot what you noticed and what you feel. Be as open and aware as you have been in the noticing in the shooting process. Stay longer with the subjects you choose than you think you “should.” Stay longer than you’ve ever thought the deserved.

Challenge yourself to create at least five (or ten) unique compositions for the subjects you’ve chosen. That does not mean take five pictures and your done. Rather, it means staying with your subject, working it and taking however many frames it takes for you to define and refine your compositions. Whatever it takes for you to leave that subject happy with the final image in the field. Do this with at least five subjects at the location. Drop the expectations and judgments as to whether a subject is “worth your time.” It is if you stopped and found something in it that held your attention. Then, when you go home, experience those images as they were created – with intention and attention.

If you want to simplify your experience even further, try using only one lens. If you do the challenge and work it – all of it – you will begin to find it easier to see the smaller stories wherever you are. You’ll be able to capture a sense of place in the smalls. You’ll recognize the value of going deeper than the landscape. You will welcome new opportunities to shoot differently, especially when the light or weather or other conditions make shooting your favorite landscapes or capturing the iconic scene “perfectly” nearly impossible.

We’ve all heard the phrase, “Go big or go home.” Well, when “big” is not an option, “Go small and stay longer.”

ASK YOURSELF SOME QUESTIONS – ASK AND ANSWER

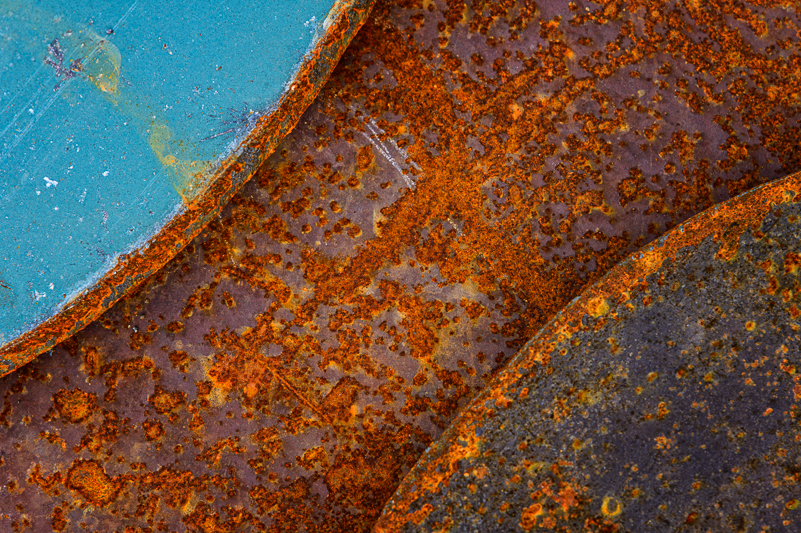

To be fair, it is easy for me to give you the challenge and follow through with a level of consistency. Finding the small picture comes naturally for me. It’s easier for me to focus on the more intimate landscapes and dive headlong into the macro world of petals, grains of sand, textures in tree bark, the rusted head of a nail in an old wood barn. I should give myself this challenge in reverse … force myself to fix my attention on the big picture, the grander landscape. In doing so, capturing the larger scenes would come easier.

A few questions in the field can help you define and refine your objectives. They don’t have to be complicated, just clear. In all of the images we make, there is something that we noticed and found interesting—interesting enough to pause and take at least one frame.

When you stop, when something holds your attention, you should ask yourself why. Why did I stop? Why here? What am I seeing? What am I feeling? And, then, you should answer the question – with specifics. For example, I like how the lines flow in this tree; I love the colors of this flower; I love the textures and colors of the peeling paint and old wood. And, I love the shapes in this pile of old railroad ties; I love the patterns and colors in the fishing nets or crab pots; I love the softness and tones in …”, and so on. Whatever it is that you notice in a scene, say it – out loud. Doing so gives you a direction, a starting point for making images that are more intentional.

Other questions that will help you with your compositions are: Who’s the “star” of the image? Who are the supporting characters? Who are the detractors? (They need to leave.) Asking and answering the questions clarify your intentions. Keep shooting until what you say you like or love or feel about the subject is staring you in the face on the back of your camera. Make sure you bring it home.

MY TAKE ON THE “SMALLS”

The images I share in this post reflect my continual process and pattern of seeing the smaller stories. As I mentioned earlier, this does not mean that I always end up in the macro world; it just depends on what I’m seeing. The series of images presented here were taken in different places. Some are more intentional than others. Most of the time, how I work a scene is closely aligned with the exercise I’ve described above.

Am I always present? No. Sometimes it’s harder to clear my mind of the “hamster wheel” of life, but I know when this is the challenge. I recognize it for what it is – a barrier and a challenge. Even still, and always, my first moments at a location or with a subject are spent without my eyes at the viewfinder. I look, I notice, I think and I feel. Then, I bring the camera in to do the work. If the big picture is part of the process, I start there. If not, I move in, and in, and in …

NOTE TO SELF: Don’t forget to take the “big picture” before I start moving in. The “where did I start” and “how did I get here” reference photos are both helpful and enlightening. In reviewing and deciding on images to share in this post, I realized that I need this reminder. Also, keep in mind that the “big picture” isn’t always pretty. Hence, the need to see and tell the smaller stories.

(With the exception of the white boots at top of this post, all the images included here were selected from a total of 416 made on four separate visits, different light, different time of day, and, yes, different “head spaces.” I can’t wait for more opportunities, and I will make myself take the “bigger” not-so-pretty picture before I begin moving in to focus on the smaller stories and unique details of the place.)

When you let go and venture “beyond the big picture,” you open your eyes and mind to new discoveries. As Andy Warhol said,

“You need to let the little things that would ordinarily bore you suddenly thrill you.”

Now, go! Go find something that peaks your interest and challenges you visually and creatively. Ask yourself the questions – why you stopped, and answer. Talk to yourself about what’s tripping your trigger.Find those things you would normally pass by, and stop.

Get lost in the little things. Let them thrill you.