What do we call visible light? We call it color. But the electromagnetic spectrum runs to zero in one direction and infinity in the other, so really, children, mathematically, all of light is invisible.

― Anthony Doerr from All the Light We Cannot See

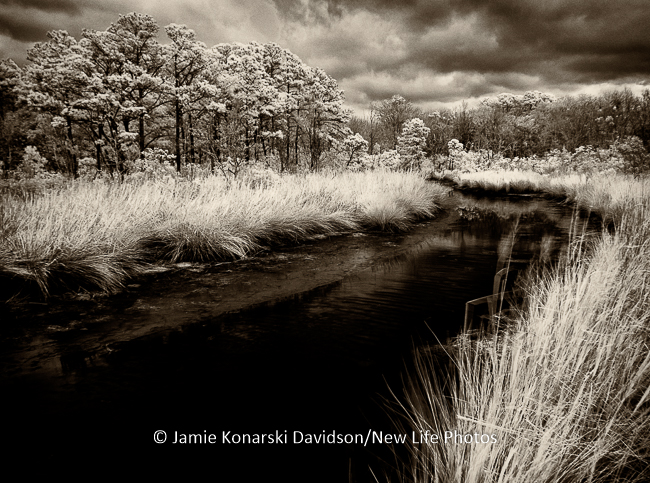

Coastal Marsh in Infrared at 590nm – Harsh midday light that was not conducive to color photography.

It’s been over six years since I was introduced – hook, line and sinker – to infrared photography. Even before I processed my first image, I was hooked (and I knew it). It began one spring day when a box from Mark Hillard containing a Canon 20D converted to 590nm arrived on my doorstep. Keep in mind, I’m a Nikon shooter and had to learn to navigate the Canon. I had no idea what a nanometer (nm) was, and my brain hurt just thinking about what I might be getting into.

I’m not a science or math geek, so words like nanometer, infrared, wavelength, spectrum and conversions made my head spin. In the end, what that early experience (or inexperience) did for me and my photography was gave me opportunities do “happy dances” in light too contrasty and “terrible” for general color photography, especially landscapes.

The other challenge for me, initially, was that I absolutely LOVE colors! All of them, though purple in any hue is my favorite. When shooting infrared at 590nm, all my images on the back of the LCD reminded me of a negative. Pretty much all color was removed, which left the bare bones of the image subject to stand on its own in form, structure, composition and exposure.

What I discovered was that shooting infrared was helping me see the landscape in ways I had not been able to before. It also helped me visualize the scene in black and white, another longstanding challenge that began to fade away the longer I embraced infrared (IR).

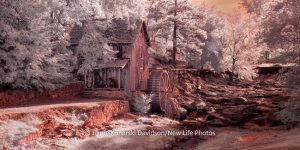

Infrared image of Gresham’s Mill in Georgia at 590nm – Processed for Faux Color after the Raw image was processed

There are endless possibilities for capturing and sharing the world of infrared. IR filters can be used, but for a more fluid shooting experience, having a camera converted to specific wavelengths (for example, 590nm, 630nm, 665nm, 720nm (standard) and 830nm (b/w) makes more sense. A number of companies offer conversions. I had my Nikon D90 converted by LifePixel and have been very pleased.

Infrared image of Gresham’s Mill in Georgia at 590nm – Processed for black/white using the Faux Color version.

I chose 590nm because it offered the possibilities for me to play with a big box of color crayons in faux color processing, and I could produce great black/white versions of those same images. Now, after only a few days of shooting with another Canon converted to 830nm, I am equally hooked to black/white IR imaging and plan to convert another Nikon body so I can experience black/white photography in ways I never have before.

There are many reasons why I love infrared photography, but perhaps the top three I will share here provide some insight into how it changed my way of seeing the world and expanded my photographic horizons.

First, IR photography breaks barriers. It is fantastic during harsh, midday light. What that means for me is that I can shoot all day long in color and infrared without limitations. When other photographers put their cameras down because the light is “bad” for color imaging, I turn to my 590nm infrared and shoot, shoot and shoot. For those who know me, I’m not a sleeper, so midday naps are unheard of for me. And, I always have snacks and water in the car, so eating is secondary to photography.

Infrared black/white barn near Cameron, NC, falling down next to a freshly plowed field. This barn has since collapsed into an unrecognizable pile of rubble overrun by vines and grass.

Second, IR photography reveals what I cannot see with my eyes. Remember, I said that I LOVE color, so visualizing the world in black and white was always a challenge for me (until infrared). It didn’t matter how much I read or knew, I just couldn’t internalize the concept. Colors always got in the way of that process. In addition, because infrared is outside the visible light that our eyes can see, it captures things that we simply cannot see, such as structure in clouds on a white-sky day.

And, third, (though not nearly approaching the end of all the reasons I love IR), IR photography provides freedom of expression. It gives me full permission to express my vision. What the camera captures in infrared doesn’t look “real.” The purest photographer, the one whose only desire is to present the world as it really is, could be challenged by IR photography at first.

I do not consider myself a documentary photographer. Rather, I embrace the idea that I am an artist with a camera as my medium. In post-processing infrared images, it’s PLAYTIME. The sessions follow a similar path of steps, but where they lead creatively is all according to the mood of the moment. With reality suspended, wider ranges of interpretation are possible, and that thrills me.

Infrared image of sunflowers in field at 590nm and lightly processed (before channel swap). Anything is possible.

The images presented here are just a few examples of what is possible when you put a converted IR camera at 590nm into the hands of an expressive photographer, however skeptical at first. Where you might go with your infrared interpretations is up to you.

Faux color infrared of Sparks Lane in the Smokies. No better way to capture an often-photographed place than with infrared and imagination. Again, this from a converted Nikon D90 at 590nm.

If you’re interested in learning about infrared photography on a more technical level, or seeing where you can go with it at different wavelengths, here are a few options: Mark Hilliard’s blog at www.markhilliardatelier-blog.com. It’s all Mark’s fault that I’m addicted to infrared. (Join Mark and me on our workshops, we cover both color and IR techniques. An IR Immersion workshop based in Pawleys Island, SC is set for this August.) Join the Infrared Photography Group on Facebook (nearly 6,000 members worldwide) at www.facebook.com/groups/Infraredphotography/. I also recommend LifePixel‘s website for lots more information on infrared photography.